LEGO fans take many shapes. Some enjoy building official sets, while others dive into their imagination. Still others take great pride in hunting down every minute variation of 2×4 brick, or in capturing beautiful images of minifigures. For some, though, LEGO is a career path. Aaron Newman has been building with LEGO all his life, and has successfully navigated the dream that many fans have: not just building with LEGO, but getting paid to do it. Aaron has been on a rocket trajectory, moving from fan to full-time LEGO artist and then to a contestant on LEGO Masters Season 1. We’ve interviewed Aaron before about his work as a fan and on LEGO Masters, but now he’s moving to Denmark as the LEGO Company’s newest designer, so I caught up with Aaron once more to learn about his journey and how he approaches building.

TBB Managing Editor Chris Malloy: Thanks for talking to us, Aaron. The last time I caught up with you was about five years ago, and you were working on your own series of custom sets, just for fun (Read Aaron Newman’s first TBB Interview here). Since then you seem to have met with what most fans would call a great measure of success—you were on the first season of LEGO Masters, and now you’ve been hired as an official LEGO set designer (Read about Aaron’s experience on LEGO Masters here). Is this the path you envisioned for yourself?

Aaron Newman: Wow Chris, it really has been a while since we spoke. I look back on where I was, who I was, and what I was up to back then; so much has changed. All the things you’ve mentioned happened, yes, but I’ve also finished school, been engaged, gotten married, adopted a dog, moved cross-country a few times… It’s been a busy past few years, that’s for sure.

Did I envision this path? Short answer: no, I could never have foreseen my journey playing out exactly this way. Long answer: if I go back and look at all that’s happened, the stepping stones on the path make sense… I did the work throughout, consistently focused on my objectives, and stayed true to my dreams, so the opportunities I’ve been lucky enough to have gotten lately feel like the gratifying fruits of several years’ dedicated effort.

Thanks in part to that last in-depth feature on TBB, my visibility as a LEGO artist really started to grow around 2016 or so. My Dragon Lands sets had possessed something of a “cult following” among a small group of Castle-loving AFOLs, but hadn’t managed to break out into the community at large until then. As a result of my work being seen by the right people, I was fortunate enough to secure my first-ever commissioned projects. I’d never built anything with LEGO for money before, and I found that I really enjoyed doing it. Of course, I appreciated getting paid to do something I loved, but I also relished the creative stimulation and the challenges of being a professional LEGO-building artist. Commission work has encouraged me to grow as a builder; I credit my paid projects more than anything else with honing my skills and broadening my range as an artist.

A pair of 1:2-scale Cavalier King Charles Spaniels Aaron built on commission.

Work begets work, and—in our social media age—views beget views. The more commissions I completed, the more inquiries I got; the more creations I shared, the more my following grew. My then-friend-now-wife Sarah, only a few days after we met, was the one who encouraged me to start an Instagram account, @aaronbrickdesigner, explicitly for my LEGO models. I think I was one of the earlier LEGO builders to start embracing Instagram as, if not the platform of the brick medium’s future, at least another site worth branching out onto; at that point, things were much more alive on Flickr. Being an early adopter on Instagram, as well as my consistent posts and careful photography, helped me to grow my following relatively quickly on that platform. As such, by the time that the LEGO Masters casting team started putting out feelers for USA Season 1 in the summer of 2019—with Instagram as one of their main venues to search on—I was somebody who came up on a few different folks’ searches.

I was totally thrilled, electrified really, when I first encountered a casting call for the show… LEGO Masters felt like a tailor-made opportunity for me, as I was somebody confident in their building skills and also “trained for TV” by my undergraduate theater degree! I’m only partially joking; while I’ve long since withdrawn from that space in favor of pursuing my LEGO art full-bore (and there’s a whole conversation to be had about that, to be sure), I’m so grateful for my acting training, for 4 years in an environment that made me comfortable on camera and lent me insight into how a casting process works.

Being on LEGO Masters was a once-in-a-lifetime, incredible, fulfilling and meaningful experience. But man, was it draining! The show was a marathon of sprints, really, where the creative, physical, and emotional fatigue only compiled from challenge to challenge. I spent a week sorting bricks when I got home, just to decompress. Still, I wouldn’t trade the time onset for anything, especially because of the amazing friends I’ve made in my “LEGO Masters Fam.” I’m sure I’ve been more articulate about my time on LEGO Masters in my exit interviews and whatnot… Overall, I’m proud of the work Christian and I put forward on the show. Though we went home sooner than we might have liked, I can (retrospectively) say that I wouldn’t change a thing, because the after-effects of that journey have been what they’ve been, which is to say, life-changing.

Aaron, second from left, on the set of LEGO Masters with teammate Christian Cowgill, host Will Arnett, and judges Amy Corbett and Jamie Berard.

My LEGO Masters exposure definitely catapulted my commissions business to the next level, putting me on the radar of some amazing clients with ambitious project ideas, which enabled me to transition to building professionally full-time. I am boundlessly grateful to have accomplished that particular goal: over the past two years, I grew my business enough that I could support myself and my little family wholly by building with LEGO. It’s a little bittersweet to be leaving behind my private business and all the work I put into it, but when the opportunity to work directly for The LEGO Group presented itself, I knew that I couldn’t say no to my lifelong dream!

While there wasn’t any direct connection from my being on LEGO Masters to my securing a position at TLG, from what I hear many designers in Billund watched LEGO Masters USA to support their coworkers, our Brickmasters Amy Corbett & Jamie Berard. Maybe more folks in the design department came to know me and my work as a result of my appearance on the show. And if so, I’m glad that they didn’t lose all respect for me after that tower collapse in Episode 5, or all the blazers I wore…

Chris: Haha, I’m sure they enjoyed your work as much as we do. Speaking of commissions, how do you determine what to charge? Mass-produced official sets are expensive already, so designing one-off models must be even more of a challenge.

Aaron: Every commission is different, and not every client is seeking the same deliverables, but there are certain key factors that contribute to a budget. I tend to think of these in two categories: labor costs (i.e., my payment) and costs of production.

I derive labor costs by setting an hourly rate for myself, estimating the time it will take me to complete each of the separate tasks necessary to complete the commission, and performing that simple act of multiplication for each line item. The tasks I’m referring to can include things like: design (usually “cost of labor: design” is the biggest expense on any budget), digital inputting, instructions fabrication, parts order & verification, photo/video editing, and more.

A LEGO version of the Salesforce Astro mascot Aaron built on commission.

Costs of production, meanwhile, refer to expenses I accrue while working on a commission. The most obvious of these—and the biggest expenditure for most projects—is the cost of bricks, but there are often plenty of other production costs. These can include the costs of packaging supplies, postage, lights/electronics used in the model, glue and adhesives if they’re being used, fabrics if they’re being used, and anything else I may anticipate needing to buy to get the job done.

With all these line items settled, I’ll combine my labor costs and my costs of production, and finally calculate a contingency and add that on top. I believe that this practice should be industry standard (insofar as LEGO-built commissions are an industry!) because, inevitably, something will end up more expensive than you originally expected. Whether that means the bricks are harder or more expensive to source, or you have to undertake extensive revision labor to perfectly match the client’s vision, or whatever else, I find that it’s useful to have a little wiggle room in the budget to ensure that you, as an artist, aren’t going in the red on a project even if something unexpected comes up.

Chris: Dragon Lands has been your ongoing project for a number of years as a fictional LEGO theme that you’ve designed as your idea of the perfect LEGO castle theme, with your models designed as “sets” in the theme. Tell us about the new wave of Dragon Lands sets. What inspired this latest round of sets?

Aaron: As you can probably tell by my having decided, “you know what, the last thirty-four Dragon Lands sets just weren’t enough for me, I need to make more”—and that I had to do this, even five years later—Dragon Lands is a pure passion project for me. This style of building constitutes the original expression of my MOCing, and this “theme” in particular has a special place in my heart. Dragon Lands is the theme I wish were real: a medieval fantasy world full of spring-loaded magic, play feature siege engines and, of course, posable dragons. Its aesthetic is informed by things like LEGO The Lord of the Rings, LEGO Vikings, LEGO Castle fantasy era, LEGO Knights Kingdom II, and an amalgam of other influences I can neither trace nor keep track of.

The most recent wave—Wave 5—has, in one form or another, been in the works since I finished Wave 4 way back in 2016. The concept of elemental dragons tied to MacGuffin-type Elemental Crystals has been a thematic through-line since my very first brainstorming for the wave. I developed a few sets back then, all of which have long since been scrapped. Like I said before, I got lucky enough to start doing commission work around 2016; this, as well as other projects that excited me, drew me away from Dragon Lands for a good while.

Sorcerer’s Cathedral (2,720 pieces) in wave 5 of Aaron Newman’s Dragon Lands.

I returned to it in late 2018 with the occasion of Bricklink’s AFOL Designer Program. I designed and submitted two Dragon Lands concepts to that contest: a dark ice dragon named Uldrak, who—with slight reformation and some recoloring work—found his way all the way to the finished lineup of Wave 5; and a coastal castle that I called “Seabreak Citadel,” the gothic keep of which eventually evolved into the Sorcerer’s Cathedral set. Neither AFOL Designer Program entry went anywhere in that competition, obviously, but working on those models was tons of fun for me, put my brain back in the set-style-building mode, and turned Dragon Lands Wave 5 from a “maybe” idea into a “definitely” idea.

The dark ice dragon Uldrak and Seabreak Citadel

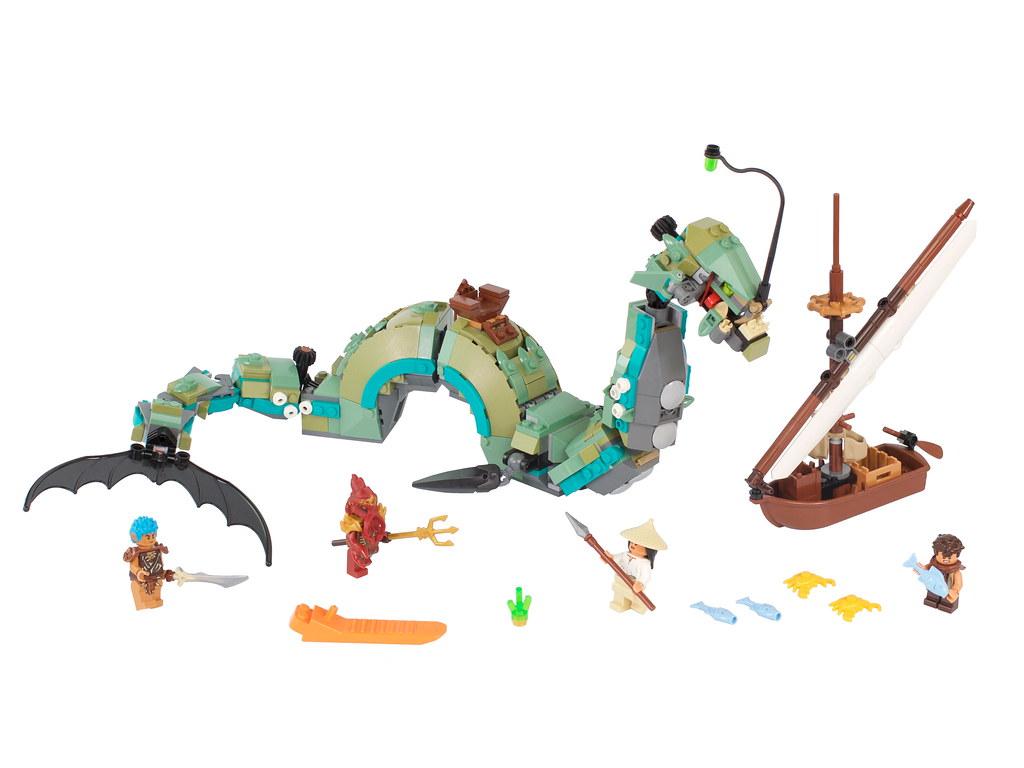

From there, I started playing around with myriad concepts for the eight-set lineup. Unlike past collections, Wave 5 features a dragon in every set, and the dragons come in unique shapes, sizes, and color combos. There are small dragons like Byre with the cathedral and the Lindworm with the ship, medium dragons like Bevyr and Uldrak that get the starring roles in their own sets, all the way up to the enormous Maelmu, the sea serpent and my biggest Dragon Lands creature ever. It was important to me that no two dragons looked alike; the closest resemblance is between Uldrak and Klariz, the ice dragon, who share a head function, but even these two I differentiated with their body types, postures and color schemes.

Even though the original Dragon Lands sets are probably out-of-memory for most folks, I nevertheless sought to break ground for the series in a few ways with these new creations. In terms of subjects, I’ve only ever done one ship (back in 2014), and I’ve never done a cathedral, so those were pretty fresh concepts I was eager to tackle. I also sought to push the “time period” of the fantasy world forward a little bit, going from “Middle Ages” towards something a little more “early Renaissance” to open up new stylistic opportunities. Lastly, I wanted the new crop of Dragon Lands sets to feel current, not just by using the modern techniques/parts/colors that weren’t available to me back in 2014-16, but also by my conscious choice to make the “cast” of the theme racially diverse, and with a more even gender balance. I’m ashamed that the first four waves of Dragon Lands included no people of color; I have since grown much more educated around issues of representation, and want to apologize to anybody who felt marginalized by the earlier sets I shared.

I hope the Wave 5 Dragon Lands sets are people’s favorites ever! They’re definitely mine. It feels fitting that some of the last creations I’ve shared before starting work at TLG are made in the “set-style” that has always been an outgrowth of my dream to be a LEGO product designer.

Chris: What’s your concepting process like? Are you someone who sits down at your bricks and starts putting pieces together immediately? Or do you design them digitally first? Sketch them out?

Aaron: Obviously it depends on the project, but by and large I design every model by hand rather than on the computer. Digital inputting almost always comes after I’ve finished a physical design. As for how I get started, that can be either with a quick sketch to figure out the silhouette, or maybe just from putting bricks together until they lead where I want them to go.

In the case of the Dragon Lands creations, I’ve got two main avenues into starting a set: a certain play feature I want to integrate, or a certain “price point,” for lack of a better word, to fill. If I’m starting with a play feature, the function leads to form; the model’s design shapes up around that function, once I’ve refined it, to best stabilize and sometimes conceal it. In the other route, if I know generally how large or small I’m choosing to go with the set, then the model becomes a puzzle around creating the iconography/key objects I want, while using only x number of bricks. The rest of the sets in the “wave” also help to inform what comes next, since I don’t want to repeat myself, and I want each set to look different from its companions.

Chris: Will people be able to buy them?

Aaron: Instructions for all of Wave 5 will be available at a future date from the Build Better Bricks website. Fabricating step-by-step instructions for models like this can be quite a time-consuming process; I don’t know when they’ll all be up on there, but they’re coming, I promise! I would have waited to share the sets until the instructions were all ready to go, but the upcoming change in my employment forced our hand on that one. The instructions for Bevyr the Swift, at least, are published on B3 as of the time of this interview.

Chris: Creating and selling instructions is becoming increasingly popular in the last few years, and you’ve been working on selling instructions for a variety of kits. Can you talk us through your process? How do you make models that are easy for people to source parts and then build at home? How much more difficult is that than just building a model to display?

Aaron: I think the proliferation of custom instructions is such a cool trend. It gives builders a new avenue for monetizing their work, if they’re seeking that… and on other side, it enables LEGO fans to experience skilled builders’ MOCs with greater intimacy than they could ever get through a gallery of images, or even at an in-person convention. The opportunity to have my designs experienced firsthand by LEGO builders around the world is one of the most exciting aspects of my new job.

I’ve designed instructions in many different contexts. As a private artist, I lean heavily on Bricklink Stud.io as my digital builder of choice for a few reasons, but the biggest is that it’s all-in-one build and instructions software. This means I can go back and forth between 3D model and 2D instructions easily to “check my work” or correct step orders if needed while I’m working on a build guide. With experience (and after countless hours poring over LEGO instruction manuals over the past 20+ years) I’ve gotten quite good at anticipating the best ways to break a model into steps and submodels while I digitally input it, which is a huge time saver when turning a digital model into something with instructions. In fact, this pattern has become so ingrained in me that now it’s a switch I can’t really turn off— even my biggest commission, a set of life-size computer replicas totaling over 10,000 bricks together, I ended up inputting in steps!

The MSI Optix Monitor & Aegis Ti5 Computer that Aaron built on commission.

Due to my “set-style” roots, I tend to value stability in my MOCs higher than many other AFOLs, who often build things in more fragile ways or using “illegal” techniques to accomplish a particular effect. No shade to them, or that kind of building—some of my favorite BIONICLE builders’ figures will shatter if you breathe on them the wrong way, but look simply stunning and are among my favorite creations out there. However, if I’m working on something where I know I’ll be fabricating instructions, I’ll push myself to over-engineer strength and stability everywhere possible, because the person rebuilding my design may not know the “strong points” on the model like I do; after all, they haven’t been handling that creation over the course of days or weeks like I have!

As for part availability, i.e., trying to fabricate a design using only easy-to-acquire bricks, that’s not always a constraint I operate under. Several of the instructions I’ve compiled in my career are for 1-of-1 models, where I’ve been commissioned to deliver not just a custom design, but also a unique build experience. In those cases, I don’t have to worry about whether FOLs at large can source a particular piece. Some of the instructions I’ve released to the public on my website contain hard-to-find pieces because they were originally designed in this context.

Of course, if you’re designing for mass consumption, you’re definitely trying at every turn to reduce overall parts costs to make the model more accessible. I’m routinely checking Stud.io’s estimated model cost as I create, whether for a single individual or for multiple potential builders, just in case there’s a randomly expensive brick in there that I could replace or work without. It takes extra effort and time, but I usually find that time to be worthwhile.

A page from Aaron’s microscale battleship instructions.

A page from Aaron’s microscale battleship instructions.

Chris: One of the things that has always set your builds apart is that many of them intentionally look like official sets. Do you think that played a role in getting hired at LEGO?

Aaron: I can’t speak to the decision-making process behind the hiring at TLG. Of course, I can joke about how the design department watching my model fall on LEGO Masters earned me sympathy points, but the reality is that I don’t know why they hired me versus somebody else. From what I’ve been told, the round of candidates I was applying alongside was incredibly qualified and competitive; I’m not sharing that to toot my own horn, more so to say that I’m sure that the design department had abundant choices of awesome people who could easily have gotten the job, had TLG been seeking something even slightly different than they sought when they hired me. The company has all kinds of criteria that their candidates need to hit, and those criteria are also always changing depending on what role(s) they’re seeking to fill at the time.

Naturally, I’d totally love to imagine that my work in set-style helped me stand out—regardless of whether that was the case—because I think of it as something of a signature focus of mine within the AFOL community, and I’m proud of that. Designing “sets” is a different breed of building than many people are used to; it demands a rigorous economy of parts use, puts emphasis on playability and stability, and values clear storytelling. I hope that the skills demonstrated by my sub-genre of MOCing felt translatable to the folks at TLG in terms of making real LEGO products. I’m certainly looking forward to discovering the differences between MOCing in set-style and making an actual set!

Maelmu the Monstrous (568 pcs) in wave 5 of Aaron Newman’s Dragon Lands.

Chris: Not all of your builds have that “official set” feel to them, however. What’s the distinction? And which style do you prefer, if you’re just building for fun?

Aaron: I’d say that, at this point in my career, the majority of things I’ve created haven’t been built in “set-style,” which last time you and I spoke definitely wasn’t the case. As much as I enjoy set-style, most of the clients I’ve worked with aren’t seeking that. More often, they want highly detailed replica builds (too complex to be sets), or display pieces (too static to be sets), or event builds (too big to be sets). There have been occasions where, like I mentioned, I’ve done commissions for folks seeking a “custom LEGO set of ______” (their home, their dog, their car, something from a video game, etc.), but even those types of models are usually built without the premise of “brick economy” that’s foundational to the purest set-style, which in my opinion seeks to emulate the mass-market sets TLG produces for children around the world.

Aaron’s model of Sauron, Dark Lord of Mordor, from The Lord of the Rings.

Aaron’s model of Sauron, Dark Lord of Mordor, from The Lord of the Rings.

It also comes down to presentation, for me. If I’m making something explicitly in set-style, I’ll do my best to match the photography that TLG uses to share its products on LEGO.com when I share my piece. I bet that I could revisit many of the models I’ve created and, just by photoshopping in a white background, I’d make them seem far more like they were built in set-style!

Building for myself, I tend to lean in a set-style direction, even if I’m not doing something as explicitly in that genre as Dragon Lands. By that, I mean to say that I defer to the principles of stability, poseability, and playfulness in most of the things I create, unless I encounter a specific problem that requires me to break from that default.

Chris: What themes will you be working on at LEGO?

Aaron: I’m starting out on the team at LEGO City, which is very exciting! Naturally, I also look forward to any chance to get my feet wet on other themes and projects— I wish I was able to contribute to everything, to be honest! I’ve already forced a few of my friends and soon-to-be-coworkers to promise that they’ll pull me back if I’m trying to involve myself in too many things at once.

Aaron at the LEGO House in Billund, Denmark.

Chris: We’ve seen LEGO hire quite a few fans to be designers in recent years. What advice would you give to other fans looking to become official model designers?

Aaron: I can only really speak to my experience and perspective on this one, so don’t take this as gospel by any means.

My advice would be to cater your approach to the opening. Do everything in your power to demonstrate you want to be a LEGO Designer, not just that you’re an AFOL who wants to build LEGO professionally. There’s a difference. There are plenty of people who build LEGO professionally (well, not plenty, but it’s a thing people can do, it’s a thing I did!); you can make your living from that if you work hard enough, you can have a great time doing that, and there are countless ways to do that. But if you want to work for The LEGO Group, you have to demonstrate to them something very specific: that you want to be a LEGO Designer, and everything that entails.

Are you ready—truly ready, eager in fact—to uproot your and your family’s lives to move to the quiet area around LEGO HQ in Billund, Denmark? Are you a good team player, somebody who can accept critique without being defensive, contribute constructively, and take on a leadership role? Do you have the mind and heart of a child, and do you love working with kids? How well do you understand the company’s values and corporate culture, and do you align with them? Do you have an education in design, and if you don’t, how can you demonstrate that you have those skills in another way? Are you able to stay creative all day, every day at work, and not get burned out? How do you perform under pressure?

Beyond that, I’d just say to never stop building, never stop pushing yourself to try new things; building outside of your comfort zone will grow your skill set. And don’t give up! Just because TLG’s opening today isn’t the right fit for you, doesn’t mean that the opening a month, a year, five years down the road also won’t be.

Chris: Thank you so much, Aaron. I wish you the best of luck with your new job at LEGO! I know I’m certainly looking forward to seeing your LEGO City sets on store shelves in a year or two.

Aaron: Cheers, Chris! I can’t wait, either.

You can find more of Aaron’s work on his flickr, Instagram, and website. Also check out other times we’ve featured Aaron Newman on TBB.

I’ve followed Aaron for some time – I got hooked by his Sauron model which along with his Ringwraith over Osgiliath take pride of place in his Lord of the Rings lego collection.