Sometime or another, you may have thought about LEGO as art or even participated in a discussion. In this Brothers Brick exclusive editorial, LEGO Ambassador Roy T. Cook (aka Imhotepidus) challenges our popular views on LEGO art. As a university professor who teaches logic, philosophy of mathematics, and the aesthetics of popular art, Roy looks at the subject of LEGO art from a different perspective and makes an argument for our misperception of LEGO creations as art. I dare you to read his potentially controversial essay:

Roy looks at the subject of LEGO art from a different perspective and makes an argument for our misperception of LEGO creations as art. I dare you to read his potentially controversial essay:

I have spoken at Brickfest (2005, 2006) and Brickworld (2008) on the topic of LEGO as art, arguing that LEGO creations can be art. In addition, I have argued that in order to be an artwork, a LEGO creation needs to incorporate three elements:

- Form: (the creation has to display some minimum of building skill)

- Content: (the creation has to express a message, emotion, etc.)

- Context: (the creation has to be situated in a larger historical or traditional context)

I am not going to rehash these arguments here – a number of you may have already heard them – especially those of you who also frequent the Research and Development section of Classic-Space.com – and I can return to these issues in the comments if appropriate. Instead, I want to suggest that we, as a fan community, are thinking about LEGO the wrong way, at least if we want to take the idea of LEGO as art seriously.

I think that the problem with the way that we think about LEGO as an art form is easy to locate, and can be illustrated by a simple example: At Brickworld 2008, a travesty occurred: My own “MOC the Line: The Man in Black (and White, and Bley)” won the Best Artwork category, while Nannan’s “Cry of Dreams” came in (a very close!) second. (No worries, however, since Nannan went on to win the coveted Judges’ Award!) Now, I am not claiming that this was a travesty out of some misguided, false modesty (since I do think that my mosaic was pretty frickin’ cool), nor am I even saying that Nannan’s creation was necessarily better (I’ll let others make that sort of judgment). What I am saying is that my mosaic had no business being judged in a Best Artwork category at all, since it isn’t an artwork to begin with. Unlike Nannan’s creation, my Johnny Cash mosaic doesn’t come with a message, or express an emotion. At best, it is a technical achievement showing off a new method for creating mosaics. This doesn’t mean it was bad, or that it had no value – it just means that is wasn’t art. The fact that it was in the Best Artwork category at all shows that we are thinking about LEGO artwork the wrong way.

I think that the problem with the way that we think about LEGO as an art form is easy to locate, and can be illustrated by a simple example: At Brickworld 2008, a travesty occurred: My own “MOC the Line: The Man in Black (and White, and Bley)” won the Best Artwork category, while Nannan’s “Cry of Dreams” came in (a very close!) second. (No worries, however, since Nannan went on to win the coveted Judges’ Award!) Now, I am not claiming that this was a travesty out of some misguided, false modesty (since I do think that my mosaic was pretty frickin’ cool), nor am I even saying that Nannan’s creation was necessarily better (I’ll let others make that sort of judgment). What I am saying is that my mosaic had no business being judged in a Best Artwork category at all, since it isn’t an artwork to begin with. Unlike Nannan’s creation, my Johnny Cash mosaic doesn’t come with a message, or express an emotion. At best, it is a technical achievement showing off a new method for creating mosaics. This doesn’t mean it was bad, or that it had no value – it just means that is wasn’t art. The fact that it was in the Best Artwork category at all shows that we are thinking about LEGO artwork the wrong way.

The problem, more generally, is that we, as a community, equate LEGO artworks with LEGO creations that resemble other art forms. Thus LEGO mosaics, LEGO sculptures, and perhaps LEGO vignettes get grouped under the technical term ‘Art’, regardless of whether they actually satisfy the criteria for being artworks. At the same time, many other creations which do seem to satisfy the criteria for being artworks – that is, they express a substantial message or emotion, etc. – are not included under the ‘Art’ heading simply because they fall into some other well-established theme or category. It is worth noting that this very blog – yes, the blog that was nice enough to invite me to write this editorial – makes this mistake in the way it categorizes posts. Just click on the category called ‘Art’ if you don’t believe me! :)

The problem, more generally, is that we, as a community, equate LEGO artworks with LEGO creations that resemble other art forms. Thus LEGO mosaics, LEGO sculptures, and perhaps LEGO vignettes get grouped under the technical term ‘Art’, regardless of whether they actually satisfy the criteria for being artworks. At the same time, many other creations which do seem to satisfy the criteria for being artworks – that is, they express a substantial message or emotion, etc. – are not included under the ‘Art’ heading simply because they fall into some other well-established theme or category. It is worth noting that this very blog – yes, the blog that was nice enough to invite me to write this editorial – makes this mistake in the way it categorizes posts. Just click on the category called ‘Art’ if you don’t believe me! :)

A few more examples:

When LEGO artist Duane Hess (Legozilla) was asked to participate in the Denver Art Museum’s “Best Spring Break Ever” this past March, members of the public were invited to help him assemble a LEGO mosaic recreation of Marsden Hartley’s painting “The Bright Breakfast of Minnie”

After all, what better way to display the potential of LEGO as an artistic medium than by using it to copy a masterpiece in another medium (insert sarcasm here)? Of course, I am not denying the value of having simple, hands-on activities that engage the museum-going public, and it is likely that this sort of consideration, and not philosophically deep considerations about the aesthetic status of LEGO, motivated choosing this particular activity to be part of the exhibit. Nevertheless, identifying LEGO art with LEGO creations that resemble artworks in other media does little to advance appreciation of LEGO as a unique art form.

After all, what better way to display the potential of LEGO as an artistic medium than by using it to copy a masterpiece in another medium (insert sarcasm here)? Of course, I am not denying the value of having simple, hands-on activities that engage the museum-going public, and it is likely that this sort of consideration, and not philosophically deep considerations about the aesthetic status of LEGO, motivated choosing this particular activity to be part of the exhibit. Nevertheless, identifying LEGO art with LEGO creations that resemble artworks in other media does little to advance appreciation of LEGO as a unique art form.

Even more appalling, in my eyes, is the ‘achievement’ of the Little Artists, John Cake and Darren Neave. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the work of the Little Artists, Cake and Neave have carved out a niche for themselves in the British Modern Art scene by recreating major works such as Damien Hirst’s “Shark Tank” and Salvador Dali’s “Lobster Phone” in LEGO (Shark Tank, Lobster Phone).

This pair have somehow become the most important LEGO artists alive by subverting the very idea that LEGO is an art form at all. As a result, the most important LEGO artworks in the world, at least in the opinion of the art world itself (Little Artists’ creations are included in the permanent collection of the Walker Gallery in Liverpool) and in terms of their price tags (the work of the Little Artists is collected by Charles Saatchi), would seem to be cute LEGO spoofs of other, important, artworks. Again, we have the idea that LEGO artworks, and in particular, great LEGO artworks, are those LEGO creations that resemble (or, in this case, are flat-out authorized forgeries of) great artworks in other art forms.

This pair have somehow become the most important LEGO artists alive by subverting the very idea that LEGO is an art form at all. As a result, the most important LEGO artworks in the world, at least in the opinion of the art world itself (Little Artists’ creations are included in the permanent collection of the Walker Gallery in Liverpool) and in terms of their price tags (the work of the Little Artists is collected by Charles Saatchi), would seem to be cute LEGO spoofs of other, important, artworks. Again, we have the idea that LEGO artworks, and in particular, great LEGO artworks, are those LEGO creations that resemble (or, in this case, are flat-out authorized forgeries of) great artworks in other art forms.

To head off at least one sort of angry response, I should make it clear that it is not the creations of the Little Artists that I find appalling – on the contrary, many of their creations are quite clever. What I find appalling is the critical reaction to these works, and the detrimental result that reactions like this have on serious thought about LEGO as an artistic medium.

To head off at least one sort of angry response, I should make it clear that it is not the creations of the Little Artists that I find appalling – on the contrary, many of their creations are quite clever. What I find appalling is the critical reaction to these works, and the detrimental result that reactions like this have on serious thought about LEGO as an artistic medium.

What we have yet to grasp, as a group (and as a society as a whole), is that LEGO is an artistic medium unto itself. LEGO creations need to resemble neither great paintings nor great sculptures in order to be great artworks. Of course, there are strong analogies between creating with LEGO and sculpting (thus, Nannan’s creations can often be fairly characterized as ‘sculptural’), but there are also differences. We should not make the mistake, however, of thinking that the more sculpture-like or painting-like a creation is, the more artistic it is.

I will conclude this essay with a call to arms. Instead of mindlessly categorizing particular LEGO creations as artworks merely because they vaguely resemble masterpieces in other art forms, we need to begin to think hard about what makes a LEGO creation a great work of art, or a work of art at all. There is little reason to think that the criteria we discover will be the same, or even all that similar to, the criteria for being a great painting or great sculpture. At any rate, we won’t find out what the similarities, if any, are unless we spend some time thinking about these issues.

I will conclude this essay with a call to arms. Instead of mindlessly categorizing particular LEGO creations as artworks merely because they vaguely resemble masterpieces in other art forms, we need to begin to think hard about what makes a LEGO creation a great work of art, or a work of art at all. There is little reason to think that the criteria we discover will be the same, or even all that similar to, the criteria for being a great painting or great sculpture. At any rate, we won’t find out what the similarities, if any, are unless we spend some time thinking about these issues.

Of course, all of this depends on the assumption that LEGO is not only fun, but can also be a medium for creating works of artistic value. At LEGO events I often run into builders who are antagonistic to this idea, typically for one of two reasons: First, some builders seem to think that thinking hard about LEGO as an art form will somehow take the fun out of building. This line of thought seems mistaken to me, since there would appear to be no reason to think that one cannot both enjoy doing something and think hard about how it is, or should be, done. Second, I get the “But it’s just LEGO! It’s just a toy! You’re taking this all way too seriously!” reaction. Of course, on one level this reaction is correct: If no one begins to take it seriously, then it will remain just a toy, and neither we nor the public will have any right to treating it as anything more. On the other hand, if we do begin thinking about the status of LEGO as a medium for the creation of art, and we develop the critical tools for evaluating and critiquing LEGO models in virtue of their artistic qualities (and not merely in terms of how complicated the SNOT techniques are, or how swooshable they are, or how cool they are), then eventually we will accumulate the theoretical ammunition necessary to convince the rest of the world that what we do is (sometimes) serious and worthy of their attention. And that wouldn’t be a bad thing, would it?

Of course, all of this depends on the assumption that LEGO is not only fun, but can also be a medium for creating works of artistic value. At LEGO events I often run into builders who are antagonistic to this idea, typically for one of two reasons: First, some builders seem to think that thinking hard about LEGO as an art form will somehow take the fun out of building. This line of thought seems mistaken to me, since there would appear to be no reason to think that one cannot both enjoy doing something and think hard about how it is, or should be, done. Second, I get the “But it’s just LEGO! It’s just a toy! You’re taking this all way too seriously!” reaction. Of course, on one level this reaction is correct: If no one begins to take it seriously, then it will remain just a toy, and neither we nor the public will have any right to treating it as anything more. On the other hand, if we do begin thinking about the status of LEGO as a medium for the creation of art, and we develop the critical tools for evaluating and critiquing LEGO models in virtue of their artistic qualities (and not merely in terms of how complicated the SNOT techniques are, or how swooshable they are, or how cool they are), then eventually we will accumulate the theoretical ammunition necessary to convince the rest of the world that what we do is (sometimes) serious and worthy of their attention. And that wouldn’t be a bad thing, would it?

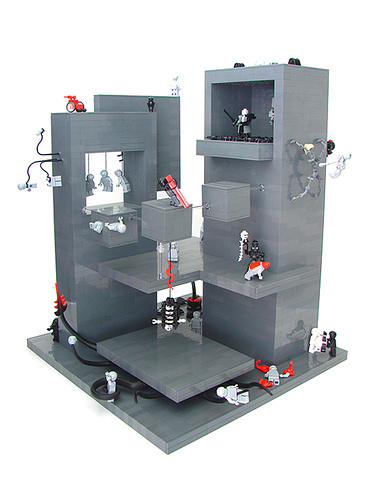

In short, Roy has urged us to re-evaluate our definitions of LEGO art. As a start, I’ve inserted a variety of LEGO creations throughout this editorial to stir up the idle brain juice inside our heads. How do you judge if a LEGO creation is a work of art? Is there a clearly defined boundary that seperates LEGO creations from LEGO art, or is there a massive gray area? If LEGO is meant to be a medium for creativity and imagination, then wouldn’t every LEGO creation be a work of art? Let your voice be heard!

[poll id=”11″]

Like this article? Tell all your friends!

Note: For those of you in continental Europe, 7979 Castle Advent Calendar has been confirmed for most of your markets. Elsewhere, there’s still some question about places like the UK, Australia, Canada, and Japan.

Note: For those of you in continental Europe, 7979 Castle Advent Calendar has been confirmed for most of your markets. Elsewhere, there’s still some question about places like the UK, Australia, Canada, and Japan.

The distinction makes sense to me. Most 10-year-olds aren’t going to mistake a set that includes dinosaurs and a four-wheeler with a

The distinction makes sense to me. Most 10-year-olds aren’t going to mistake a set that includes dinosaurs and a four-wheeler with a

Applying this philosophy to my LEGO hobby, I don’t believe LEGO sets that depict realistic or modern military themes — including soldiers, military vehicles, and historical conflicts — are appropriate for children ages 5 to 12. Other toy companies certainly don’t agree, taking advantage of patriotic fervor and every boy’s fascination with guns. And yet, this is one of the very reasons I respect LEGO and their no-military policy. They stand apart from the rest.

Applying this philosophy to my LEGO hobby, I don’t believe LEGO sets that depict realistic or modern military themes — including soldiers, military vehicles, and historical conflicts — are appropriate for children ages 5 to 12. Other toy companies certainly don’t agree, taking advantage of patriotic fervor and every boy’s fascination with guns. And yet, this is one of the very reasons I respect LEGO and their no-military policy. They stand apart from the rest.